Today we share a synthesis of the UMAS overview of the discussions about the roadmap to Net Zero GHG from the IMO MEPC 80:

On July 7, 2023, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) achieved a significant milestone in the global shipping industry by adopting its 2023 IMO GHG Strategy. This revised strategy builds upon the 2018 Initial Strategy and establishes a momentous day for international shipping in its efforts to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

A notable enhancement in the 2023 Strategy is the inclusion of the concept of a Just and Equitable transition, which was absent in the Initial Strategy. This revision sets forth expectations for the sector, as well as the development of future policy measures, to strive for substantial GHG reductions. Specifically, the strategy aims for a 30% reduction in GHG emissions by 2030, 80% reduction by 2040 (based on 2008 levels), and an overarching ambition of achieving net-zero emissions as close to 2050 as possible. This represents a significant strengthening of the initial strategy and sends a strong signal to the shipping sector.

Moreover, the 2023 Strategy introduces a new level of ambition derived from the collaborative efforts of UMAS, the High Level Climate Champions, and the Global Maritime Forum. This involves the adoption of zero or near-zero GHG emissions technologies, fuels, and energy sources to account for at least 5% (aiming for 10%) of the energy used by shipping by 2030. This commitment encourages early investments in long-term solutions, paving the way for the emergence and increasing adoption of zero-emissions technologies and supply chains starting from 2030.

In terms of content, the strategy expands the scope of discussion from carbon intensity to GHG emissions, incorporating a well-to-wake perspective that considers the full lifecycle of the fuel. Additionally, the strategy provides a clearer indication of forthcoming global measures, including the adoption of a goal-based marine fuel GHG intensity standard and a maritime GHG pricing mechanism by 2025. However, the strategy falls short of aligning the sector’s reduction targets for 2030 and 2040 with the pathway necessary to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius or below. Consequently, further work on the GHG reduction pathway is anticipated when the strategy undergoes revision in 2028.

Overall, the 2023 IMO GHG Strategy represents a multilateral compromise that unites Member States behind a stronger set of reduction signals. It now requires the concerted efforts of both the shipping sector and policymakers to implement these signals effectively.

Questions regarding the CO2 and GHG roadmap to Net Zero 2050

Does this new strategy align with limiting temperature rise to 1.5°C?

No, the new strategy does not align with limiting temperature rise to 1.5°C. The greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction pathway described in the strategy, with indicative checkpoints of 20% and 70% GHG reductions based on 2008 levels, falls short of the guidance provided by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) for meeting the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement. However, the Revised Strategy commits the International Maritime Organization (IMO) to strive for higher GHG reductions of 30% and 80% by 2030 and 2040 respectively, still based on 2008 levels. While these targets are not fully aligned with the IPCC’s guidance, they are closer to the desired trajectory. By combining further actions by the IMO, as well as national, regional, and industry initiatives, it becomes more feasible to achieve a GHG reduction pathway that aligns with the 1.5°C goal.

Will these numbers (the levels of ambition and checkpoints) change again?

Most likely, yes. The strategy is scheduled for further revision in 2028, and subsequently every five years. Many countries have expressed support for Science-Based Targets initiative (SBTi) targets derived from the IPCC’s scientific recommendations, which entail a 37% reduction by 2030 and a 96% reduction by 2040. If GHG reductions fall short in 2030, the pressure will persist for these targets or potentially stronger ones. By 2028, there will be a greater understanding of technologies, fuels, and the impact of climate change, leading to increased political pressure for action. It is plausible that the targets will be revised upwards. If the 30% target is secured as a new minimum, then, based on the IPCC’s current guidance (which may change by 2028), the sector may face the challenge of achieving approximately 100% GHG reduction by 2040.

Are offsets on or off the table?

Neither. The debate during ISWG-GHG 15 focused on the 2050 target revealed that the majority of countries preferred the term ‘zero’ or ‘net zero’ without including offsetting. However, some countries supported the term ‘net zero’ and suggested a limited role for offsetting if it becomes impossible to reduce the remaining small percentage of emissions. In an attempt to bridge the divide, the chair proposed excluding explicit mention of offsetting from the language, using constructive ambiguity. Therefore, the issue of offsets is likely to resurface in the discussion on mid-term measures. The majority opposition to offsetting is relevant in considering the likely outcome of that debate. The current strategy’s checkpoints specify ‘total annual GHG emissions from international shipping’ without the mention of ‘net.’ If offsets are considered at all, it is more likely to be in the context of the final stages of the fuel transition and not as a reason to delay the transition. Analysis indicates that offsets may become increasingly expensive over time, as meaningful offsetting requires sectors to forfeit their own emission reduction efforts. Furthermore, offsetting would likely play a minor role in shipping’s transition due to the need to shift away from fossil fuels and stimulate the use of alternative fuels and energy sources.

Does the strategy stimulate a transition to new fuels?

Yes, the strategy does stimulate a transition to new fuels. Shipping has both near-term options, such as improving efficiencies and using drop-in fuels like biofuels, and long-term options necessary to achieve zero emissions, such as renewable energy-derived fuels like green ammonia. One of the challenges in this transition is ensuring early adoption of the more expensive long-term solutions, including in regions with low-cost production potential. This coordination between ship machinery changes and investment in land-side production and supply chains presents a “chicken and egg” problem. Early deployment of long-term solutions alongside nearer-term options is crucial for cost reduction, infrastructure development, training, and safety standards. Therefore, many industry stakeholders have advocated for a 2030 goal of achieving a minimum volume (e.g., 5%) of zero-emission fuels. The policy measures and a more precise definition of “zero or near-zero GHG emission” technologies will be determined during the adoption of mid-term measures, expected in 2025. During the debate, most member states rejected the inclusion of “low GHG” as it implies more support for certain biofuels, while “zero or near-zero” better represents hydrogen-derived fuels, which are expected to play a key role in achieving deep GHG reductions.

Are the reductions tank-to-wake or well-to-wake, on CO2 or GHG?

The reductions considered in the strategy are well-to-wake and encompass all greenhouse gases (GHGs). During the debates, a clear majority of member states supported ambitions and targets based on well-to-wake and GHG reductions. The strategy now includes a clearer focus on GHG reductions, which includes methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions, in addition to carbon dioxide (CO2). While there remains a carbon intensity target for 2030 related to the review of the short-term measure, the overall framing and scope of the strategy consider GHG reductions and well-to-wake emissions. The strategy emphasizes that GHG emissions from marine fuels should be accounted for based on the lifecycle GHG intensity guidelines developed by the organization. This comprehensive approach ensures that issues like methane slip associated with liquefied natural gas (LNG) production and use as a marine fuel are accounted for, including when setting policies to achieve the 2030 checkpoint. The strategy also recognizes that hydrogen-derived fuels should be accounted for based on lifecycle GHG emissions, taking into account upstream emissions from fossil fuel-derived hydrogen production if carbon capture is not employed.

What will be needed to meet the 2030 target in practice?

To meet the 2030 target, a combination of maximizing efficiency options and utilizing alternatives to fossil fuels will be required. The optimal solution will vary depending on the ship type and operating area. Forecasts from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) can provide an estimate of the necessary improvements and changes compatible with both the 20% and 30% reduction targets. Various fuel mix scenarios for 2030, including biofuels, liquefied natural gas (LNG), hydrogen-derived fuels, and conventional fuels, have been considered. These scenarios align with the strategy’s language regarding near-zero and zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emission technologies and fuels. Based on conservative assumptions about the GHG intensity of different fuels in 2030, calculations reveal the required improvements in CO2 intensity, efficiency, and GHG intensity as average values across the fleet. The exact level of progress made by 2023 is unknown, but estimations indicate a ~32% reduction in CO2 intensity compared to 2008. Focus will now be placed on determining the actual level of efficiency and GHG intensity reduction needed to achieve the objectives.

What will be needed to meet the 2040 target in practice?

Meeting the 2040 target will necessitate a near-complete shift from fossil fuels to hydrogen-derived fuels. The targets require a 90-95% reduction in the average ship’s GHG intensity. This level of reduction cannot be achieved solely through fossil fuels and efficiency improvements. It will require sustained growth in renewable electricity, green hydrogen production, and the synthesis of hydrogen into suitable marine fuels. Innovation will continue to play a vital role, and the most attractive and competitive options are expected to become clearer throughout the 2030s. The strategy’s 2030 target of achieving a 5% volume of zero-emission fuel will stimulate pilots, trials, and increased deployment, further driving the transition. By 2040, a significant shift to hydrogen-derived fuels is expected.

What about CII and EEXI, what will happen to these?

The Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) and Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (EEXI) will need to be revised upwards, with increased stringency set for the period leading up to 2030. The revision process is already scheduled to be completed by 2026, but there may be an effort to expedite it to provide certainty on their future role sooner. The revision will address various aspects, including the possibility of converting them into energy efficiency regulations instead of focusing on carbon intensity, the metric used, and enforcement methods.

Has a levy disappeared? What policies can we expect to drive the transition?

The levy has not disappeared; it has been renamed. It is expected that shipping’s transition will be driven by a combination of a fuel standard and a greenhouse gas (GHG) price. The fuel standard will regulate the phased reduction of GHG intensity in marine fuels, while the GHG price will increase the cost of fossil fuels and generate revenues. The specifics of these measures have yet to be defined, but proposals and design options will be further developed and decided upon at the next meeting, MEPC 81. The meeting at MEPC 80 focused on setting ambitions rather than finalizing measures. A comprehensive impact assessment will be conducted, and the results will guide further discussions at MEPC 81. Different measures, such as GHG credit trading and fee-bate mechanisms, will be considered. Member states’ preferences for measures indicate support for a levy or per-tonne pricing mechanism combined with goal-based technical measures. The aim is to facilitate a just, fair, and equitable transition.

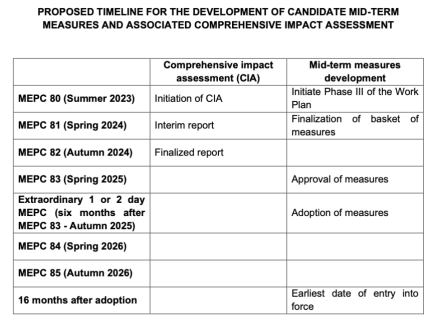

When can we expect measures that will implement these targets?

Clarity on measures can be expected by the end of 2025, and the earliest entry into force would be in 2027. The measures are scheduled for adoption in 2025, and important signals about their details will be available throughout 2024. The schedule is driven by the need to finalize the measures’ details, which depend on the results from the Comprehensive Impact Assessment and discussions between states. There are also minimum periods required between the key steps in the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) process, such as approval, adoption, and entry into force.

What are the implications for shipping-related investments?

The Revised Strategy has significant implications for both renewable energy and fossil fuel investments. The strategy sets expectations for GHG emissions reduction targets and promotes the uptake of zero or near-zero emission technologies, fuels, and energy sources. This signals a need for immediate investment in such solutions. Investors may prefer higher certainty, which will come when the strategy is converted into a policy in 2025. However, waiting for certainty may pose risks or missed opportunities. National governments, industrial strategies, regional policies, and industry actions will be important in lowering investment risks and costs.

Will IMO policy stimulate use of revenues across countries “evenly”?

A: It is too early to tell, but there are indications that opportunities in the global south will be assisted. The IMO’s strategy envisions a just and equitable transition, which includes leaving no country behind. The strategy signals a commitment to facilitating the role of developing countries, Small Island Developing States (SIDS), and Least Developed Countries (LDCs) in the transition. This suggests that the deployment of revenues from GHG pricing may not be evenly distributed between all countries. The design of the measures and the response from the sector will provide further signals about potential investment patterns.

What are the implications for trade, and how might remote developing countries be affected?

The impacts on trade will depend on the development of the basket of measures at the IMO, the outcome of the Comprehensive Impact Assessment, and the response from the shipping sector and stakeholders. Remote developing countries, heavily dependent on imports, may already experience high shipping costs. Export-driven developing countries trading low-value bulk goods or far from target markets have concerns about the impact of global and regional measures on trade patterns and import costs. The Comprehensive Impact Assessment will provide more detail on the impacts of measures and address disproportionately negative impacts.

What do the dynamics of this meeting imply about the nature of IMO’s further work on GHG?

The dynamics of the meeting were positive and set a positive momentum for further work. Unlike in 2018, all Member States were onboard and supporting the adoption of the 2023 strategy. The unity among Member States is valuable as the IMO proceeds with the development of measures. An IMO-led transition for the industry is seen as more effective, less costly, and more equitable than regional actions. The global nature of the IMO makes it the appropriate forum for regulating the shipping sector.

What does this mean about shipping’s inclusion in EU ETS?

The inclusion of the shipping sector in the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS) remains unclear. From January 2024, the EU ETS will apply to the shipping sector, covering internal EU voyages and 50% of CO2 emissions from ships entering or leaving the EU. The scheme will extend to cover GHG emissions from 2026. Depending on the adoption of a global market-based measure by the IMO, the EU may review its inclusion of shipping and decide on a different course of action. However, there is no obligation for the EU to take further action beyond reviewing the situation. If the IMO does not adopt a global market-based measure by 2028, the EU will consider alternative measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from maritime transport.

Source: UMAS