According to the report of “The Impact of Alliances in Container Shipping”, it is possible to highlight the connection between alliances and overcapacity, the loss of reliability in the service itineraries and the long waiting times. The concentration in shipping alliances may be now days the start of an oligopoly:

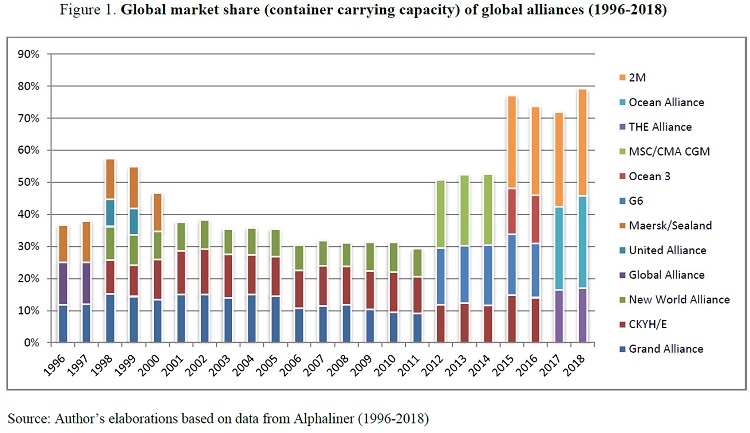

Alliances emerged in the mid-90s promoting cooperation between smaller lines. Now, the lines in the alliances are now the global ones (2M, OCEAN and THE Alliance) that began operation in 2017 containing the 8 largest lines in the world. Together they account for 80% of the containerized transport market and operate 95% of the world capacity in services from East to West, the largest containerized flow.

Over the years and the increase in world trade, the lines have strived to achieve better economies of scale and reduce their marginal costs through the purchase and operation of containerized mega ships. These new constructions are possible by the same alliances since it helps them to reduce costs and share the risk of filling the ship with other lines that basically comply with the same transport service.

The containerized mega-ships have fueled the overcapacity of the market and according to the report, there is a correlation between alliances and excess capacity. Although the Alliances have made the supply of maritime transport more uniform and make differentiation more difficult, they have also contributed to the reduction of service frequencies, fewer direct connections from port to port, affecting itineraries and increasing timeouts.

These effects materialize in higher inventory and storage costs for exporters and also, a change in the alliance or service has the multiplying effect because it affects all customers of the member lines. At the same time, the alliances have concentrated the port networks, since by joining they manage to have a much stronger power of negotiation and decision to decide the ports of arrival. This directly affects port operators and port service providers such as pilots and tugboats, among others. Finally, in the port industry, it reduces the rates of return on investment of all the interest groups and increases their pressure.

The participation of container lines in port terminals has increased from 18% in 2001 to 38% in 2018, which may cause concern since the terminals dedicated to these lines can exclude the other lines. Similarly, investments in terminals increase entry costs, which would make the containerized transport market less competitive.

However, the alliances also function like an interest group that exerts pressure for the improvement of the port infrastructure of the terminals with public funds that can later be unprofitable depending on the fluctuation of the port service demand and the power of the alliance to change.

In terms of freight, excess capacity has allowed its reduction and this cost savings have been offset by additional costs for exporters such as storage and inventory. Likewise, it limits the risk diversification strategies of exporters and cargo agents.

Finally, the alliances could present competition problems since the concentration of the four main operators represents 60% of the global container transport market in 2018. In the case of Maersk, with a participation of 19% it represents more than the participation of any alliance of shipping lines before 2012 and completely changes the panorama of what an alliance of containerized lines meant at the time. In conclusion, the alliances generate abnormal entry barriers and may allow the lines to share confidential information of the cost structures between them.